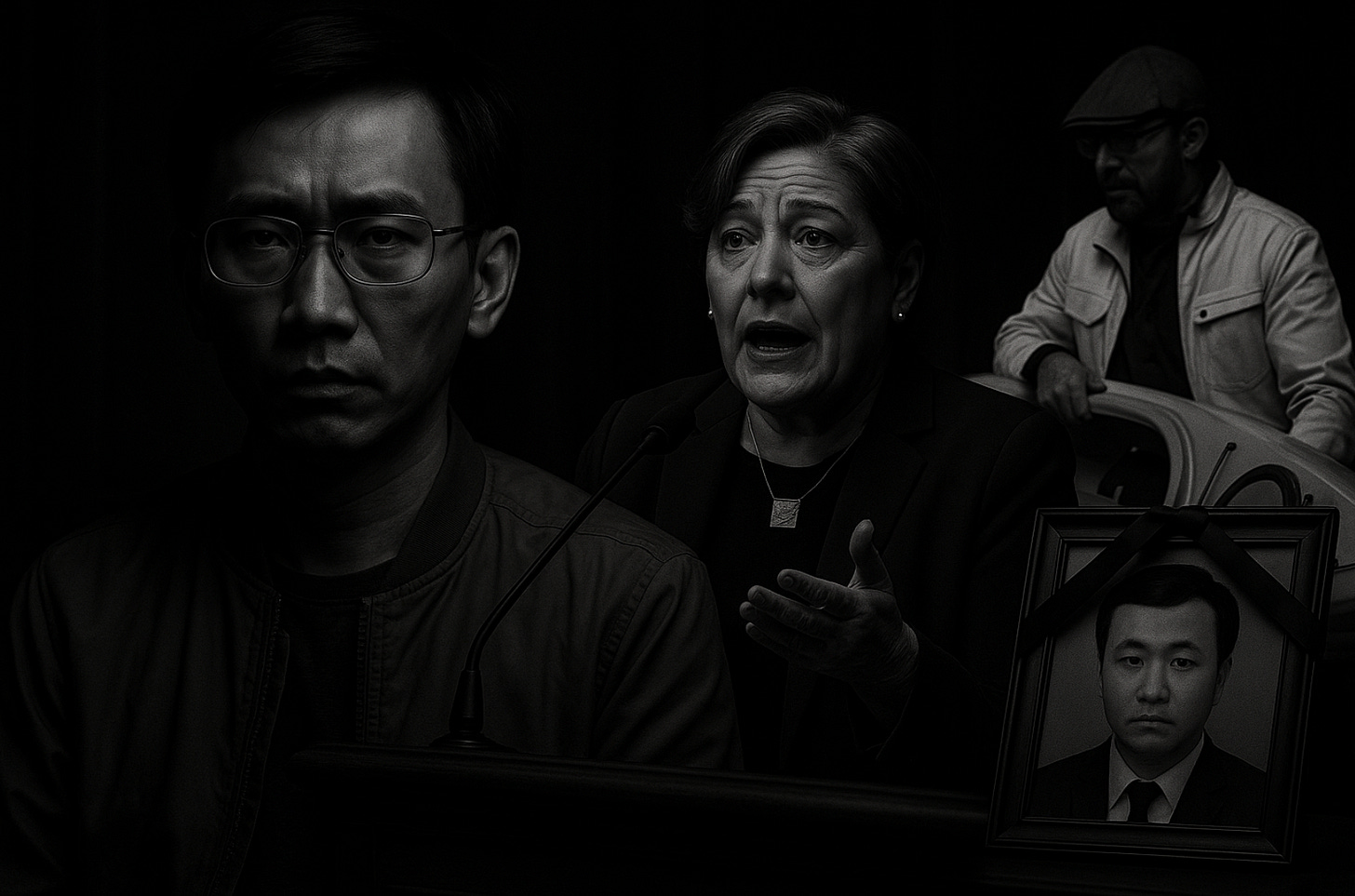

‘Our superiors ... want to get rid of him’: Digital messages reportedly allege Chinese police targeted dissident who died suspiciously near Vancouver

OTTAWA — Radio-Canada, drawing on digital records first disclosed to Australian media in 2024 by an alleged Chinese spy, has reported new evidence suggesting that a Chinese dissident who died in a my…