New York Congresswoman Grace Meng’s Office Drawn Into Landmark United Front Case as Staffer Appears in CCP-Linked Linda Sun Chats

BROOKLYN — In a masterful closing argument, strategically tailored for a mainstream American audience with no prior knowledge of Chinese Communist Party statecraft, U.S. prosecutor Alexander Solomon walked a jury through what appears to be the most clear-cut, open-court narrative yet of how Beijing allegedly seeks to subvert Western leaders through diaspora interference schemes, and dropped bombshell after bombshell.

Among the most striking: a diaspora leader working for Beijing’s United Front political-influence arm, who tasked senior New York State employee Linda Sun with advancing China’s interests by influencing Governors Cuomo and Hochul, also had a deputy inside his United Front organization who was simultaneously employed by New York Congresswoman Grace Meng, according to case evidence.

That phrase — “United Front front organization” — is powerful. For years, intelligence services in the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom have used similar language in classified and public warnings: the United Front Work Department cultivates “overseas Chinese” elites, business associations and friendship groups to build influence channels into Western politics.

But this was not the kind of explanatory narrative many of The Bureau’s readers are used to. We have built out, iteratively, year after year, reporting on the deep architecture of President Xi’s United Front “magic weapon” — the overseas political-influence and intelligence system described in Chinese documents and Western scholarship. Solomon met the jury at a beginner level and built Washington’s case plainly and painstakingly.

He started, quite deliberately, with a network every American relates to: family and friends.

“Now, the first thing I want to talk about is the cast of characters. You heard a lot of Chinese names in this case and it may have been a little confusing to follow even if you speak Chinese.”

From there, he layered motive, structure, and money — until what counter-intelligence officials usually discuss in classified briefings was laid out for 12 ordinary New Yorkers, step by step.

The cast: family, friends, and the consulate

Solomon began at the center: the defendants and their immediate circle.

“First of all, there are the defendants, Linda Sun and Chris Hu. You obviously know who they are. You’ve seen them every day here in court,” he told jurors. He walked them through Sun’s Chinese name — “in documents and especially Chinese documents, Linda Sun is often referred to by her Chinese name Sun Wen. Sometimes she’s referred to as Linda Hu” — and Hu’s aliases: “And Chris Hu is referred to as ‘the Orphan’ or his Chinese name, Hu Xiao. That’s how he is referred to in his electronic chats.”

Then came the inner orbit. Sun’s mother Mei Ping Sun, who testified at trial; family friend and “distant relative not by blood” Henry Hua, whose name appears in bank records; Hua’s wife Lian Wang, whose name is on massive checks; business partner Jay Chen, who co-owns a liquor store with Hu; and logistics operator Chris Zheng, whose firm Seko/Air-City “is the same company that Chris Hu uses to send some lobsters to China.”

Over in China, he reminded jurors, sits Chen Xiaoshi, nicknamed “Coca-Cola Chen” for his propensity to guzzle the soft drink.

Chen is “Chris Hu’s uncle based in China,” Solomon said, “and also Chris Hu’s partner in the lobster business,” and the man who “sends money to Chris Hu through wire transfers in other people’s names or through a woman named Sandy Hong.”

Only once that web was in place did Solomon turn to the second ring: “the people at the Chinese consulate here in New York City, people who were giving orders to Linda Sun.”

At the top is Consul General Huang Ping.

“He’s the person whom Linda Sun would often call the Ambassador. So he’s got a private chef who makes salted duck, which apparently is a delicacy. Huang Ping is the one who gave most of the orders to Linda Sun.”

When Sun did what the Consul General wanted, Solomon said, she would “sometimes ask him to have a driver from the Consulate deliver a duck all the way to her parents’ house in Flushing. Sometimes she wanted enough duck to feed her family for Thanksgiving dinner.”

Below Huang, jurors were reminded of Li Lihua – “the woman that Linda Sun allows to secretly listen in to a New York State government call,” and who “asks Linda Sun to record Lieutenant Governor Hochul in a Lunar New Year’s greeting.”

There was also Xi Shen, “another member of the Consulate that Linda Sun talks about what she’s doing for the Chinese government,” who at one point receives information Sun pulled from “an internal New York State database.”

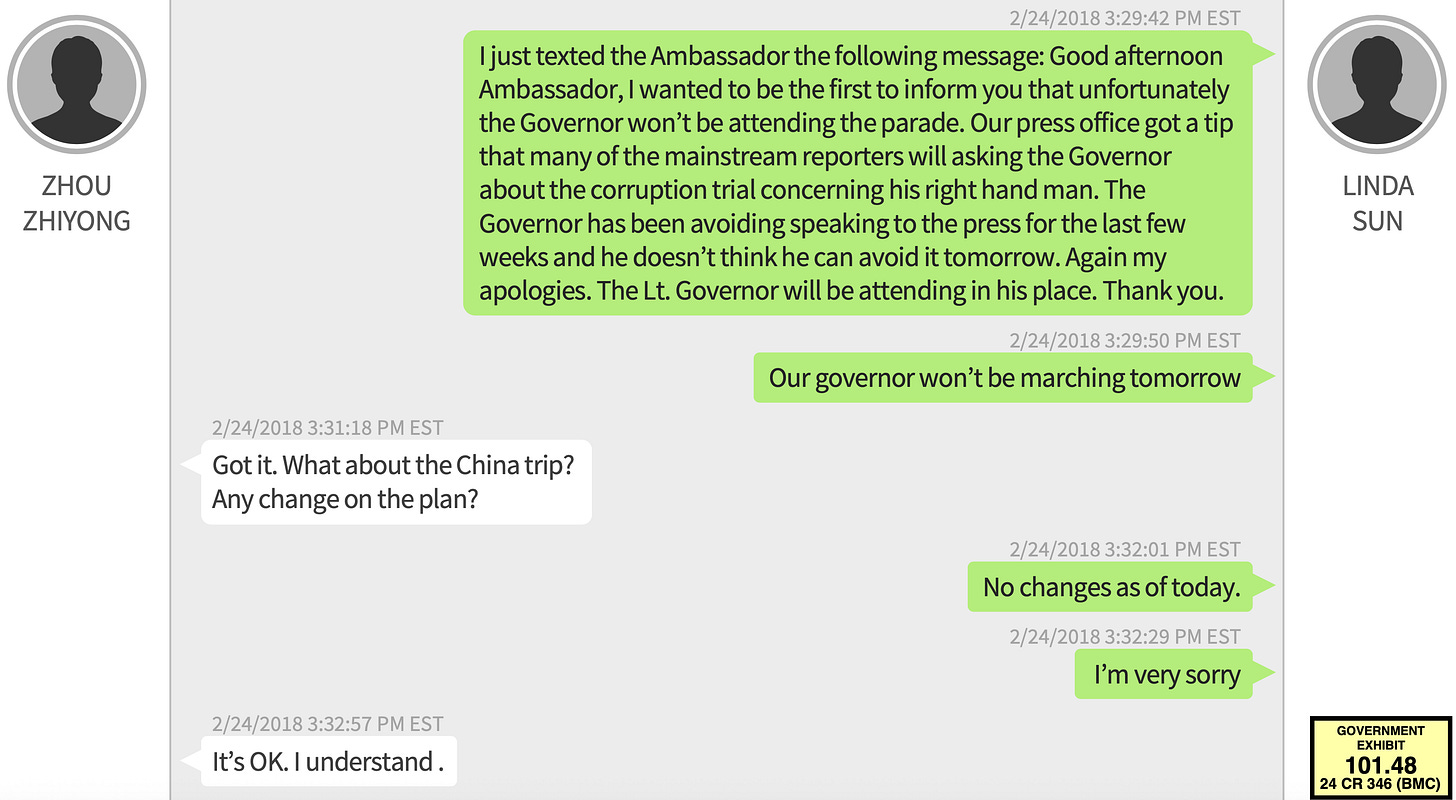

Next, referring to a source of evidence every single American citizen is familiar with – text messages – Solomon drove home who Sun was really working for, in the U.S. government’s telling.

“You saw a bunch of text messages between Linda Sun and the Consulate that probably made you shake your head,” he told jurors. “She did not hesitate to tell the Consulate, and this is the PRC government, the innermost secrets of New York State government.”

“Then there are her demeaning depictions of Governors Cuomo and Hochul,” the prosecutor continued. “These are extraordinary communications, like the way she told Li Lihua that she could control Hochul’s schedule better than Cuomo’s.”

Pausing slightly for impact, Solomon, an orator who speaks so rapidly that court stenographers struggle to keep up, let this question hang in the air.

“Why does the PRC Consulate need to know that Linda Sun thinks she can treat Hochul like her puppet?”

Having drawn the New York Consulate network, Solomon turned to their purpose.

“So the next question you need to think about is what does the PRC Consulate care about? What do they want Linda Sun to do?”

Rather than invoke words sometimes used in The Bureau’s United Front lexicon such as “transnational repression” or “CCP political warfare,” he reached back to earlier expert testimony from law professor Julian Ku, who had described Beijing’s so-called “Five Poisons.”

Ku testified, Solomon reminded the jury, “that basically, the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party are really fearful of activists outside of China who care about certain topics. The main one is Taiwanese independence. Whenever U.S. or local leaders engage with Taiwanese government or leaders, China goes kind of crazy. That’s because they think Taiwan is a runaway state that should be part of regular China.”

“Another one of the Five Poisons,” he continued, “is the Uyghurs. The Uyghurs are an ethnic minority based in China who have suffered mass incarceration. A lot of people think that mass incarceration is not a great idea and they protest. But China takes offense and thinks that that issue is an internal domestic issue to China.”

Then came the hinge sentence that connects distant geopolitics to Albany.

“So basically, the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party, which I’ll sometimes refer to as the CCP, don’t want overseas Chinese people taking Taiwan’s side or the Uyghurs’ side. And one of the ways that Linda Sun served the Chinese government and the CCP was by keeping Taiwan as far away as possible from the governor’s office, and by keeping the Uyghurs out of official statements.”

For people who have read Canadian and Australian intelligence warnings, that line is familiar. For a U.S. jury, it is the translation key.

This is why PRC officials care what a New York lieutenant governor says on Lunar New Year videos, and this is why they care who the governor meets in Manhattan offices.

The local bosses: hometown associations as levers

Solomon’s next step was to introduce what Xi’s speeches call the “magic weapon” of the United Front: local association leaders who sit between the consulate and the diaspora.

“The next and final group of characters I’m going to talk about,” he said, “are the leaders of the local associations. There is a lot of complex testimony here, so I’ll go slowly.”

“There are two main local leaders that Linda Sun is in touch with,” he explained. “They both report to the Chinese government, keeping Consul General Huang Ping apprised of what they’re doing.”

The first is Fuyin “Frank” Zhang — “the head of a local group of Chinese people from Henan Province, and president of the Henan Hometown Association.”

His first deputy, Xiqing “Sydney” Li, “is an employee of Congresswoman Grace Meng.” That one line quietly expands the reach of the U.S. government case, tying the Henan hometown machine allegedly used by Beijing to corrupt Linda Sun, into yet another senior American government office.

In one key government exhibit, a WeChat thread captured on a device labelled “SYDNEY” shows how Congresswoman Meng’s staffer and Zhang Fuyin are reporting up the chain about Sun’s role.

Writing to a PRC “Director Wang,” Zhang thanks him for securing a speaking slot for Linda Sun at a Free Trade Pilot Zone Development Forum, and proposes that she speak on “Sino–US economic and trade relations” and New York State’s trade ties with Chinese provinces — a framework he notes was recommended by China’s Ministry of Commerce.

It’s an important point. The text messages suggest that the push for deepened trade and joint projects between Henan Province and New York State was set at the top of Beijing’s leadership.

And Zhang was seeking to place his prize asset, Linda Sun, into the upper echelons of international trade discussions.

He urges that her draft speech be rushed to provincial leaders for approval. The exchange underlines how Zhang and his deputy, Sydney Li — who at the same time draws a paycheck from Congresswoman Grace Meng’s office — were presenting Sun to Beijing as a de facto voice for New York in front of Party-guided provincial audiences.

The second “community leader” is Qianping “Morgan” Shi, who shows up again and again in chats with Sun, in meetings with officials, and in business favors for Sun’s husband, Chris Hu.

A third local leader, Liang Guanjun, provides the legal anchor.

Solomon reminded jurors that Liang’s association had registered under the Foreign Agents Registration Act — “the same statute that Linda Sun is accused of violating in this trial” — and pointed them back to video of a 2019 protest outside Grand Central Station against a visit by Taiwan’s president.

Liang “is one of the people who is outside Grand Central protesting, right next to Linda Sun,” Solomon said.

“He’s the one in the middle, yelling things like, for the Taiwanese leader to go home,” Solomon told jurors.

Solomon reminded them that they had already seen text messages showing that Liang “helped Chris Hu’s business in Guangzhou Province.”

Again, geopolitics and money move together.

The man chanting against Taiwan on camera is, in the government’s account, the same figure smoothing the path for Hu’s trade deals. And scenes like this are not unique to New York. The Bureau’s open-source analysis and diaspora source accounts suggest that similar heated protests, seeking to drown out mass democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong, played out across Western capitals in 2019, driven by the same networks and the same political aims.

Bid to build Chinese colleges in New York

With the players and ideology laid out, Solomon shifted to the first major alleged scheme: Henan’s push for educational projects and political access in New York.

“So putting Liang Guanjun to the side, let’s focus again on Frank Zhang and Morgan Shi. What were they up to?” he asked.

“Frank Zhang was taking orders from the government in the Henan Province. The Henan Province wanted to set up cooperative educational projects with New York State, something about building campuses both here and in Henan. These projects would involve millions and millions and millions of dollars.”

“The details of the project don’t really matter for the purpose of the trial,” he told jurors, “but the broad idea is that there was a lot of money at stake and it helps you understand people’s motivations.”

For Henan officials, he argued, “a lot of money was at stake, and they badly wanted to send official delegations here to New York State to meet with Governors Cuomo or Hochul. And they really wanted Cuomo or Hochul to come to visit them in Henan Province.”

“One of the things that Linda Sun did for the Chinese government,” he continued, “is try to make these visits happen.”

But there was a hitch.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bureau to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.