Breaking: China’s Secret Police Got Real-Time Intelligence on Tory Leadership Race

Beijing’s Eyes in Westminster: Collapsed UK Spy Case Exposed Real-Time Flow of Intelligence to China.

LONDON – “You’re in spy territory now.”

The warning came through an encrypted chat on 19 July 2022, sent by Parliamentary researcher Christopher Cash to Christopher Berry, a British teacher working in China. According to newly released documents on the Chinese espionage scandal now shaking the British government, Berry had just met in Hangzhou, Zhejiang, with a senior Chinese Communist Party leader.

Within hours, the young British teacher relayed details of that meeting to Cash in London — who, investigators say, had been collecting sensitive information on the Parliamentarians he worked for: a group of Conservative MPs critical of Beijing and therefore evidently deemed threats to the Chinese state.

Berry, in turn, was passing that intelligence to his handler, a man identified only by the codename “Alex,” believed by British counter-terrorism police to be working for a front organisation controlled by China’s Ministry of State Security — the regime’s powerful secret police.

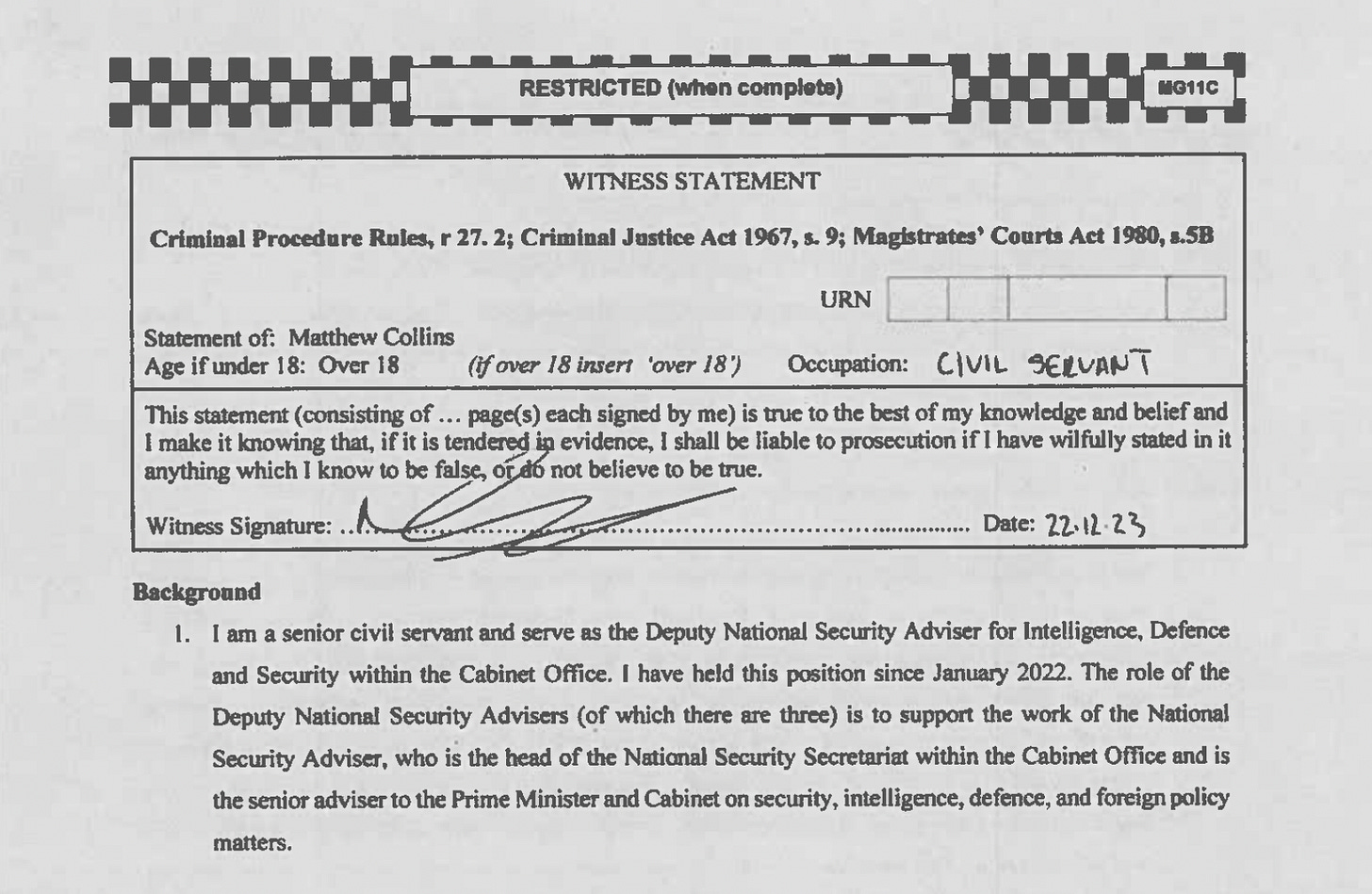

In his witness statement for the prosecution against Berry and Cash, the UK’s Deputy National Security Adviser Matthew Collins wrote that “it is highly unlikely one of the most senior officials in China would meet with Mr. Berry unless the Chinese state considered him to be someone who could obtain valuable information.”

Collins said the short turnaround in Berry’s reporting indicated that Beijing used it to “inform real-time decision-making.” In his assessment of the evidence, Collins described these two elements as “particularly striking.” The first was the urgency with which taskings were issued and completed. “There are examples in the messages exchanged between Mr Berry and ‘Alex’ of the latter requesting information from him as a matter of urgency,” he wrote, adding that “on one occasion, for example, a total of thirteen hours passed between Mr Berry receiving a tasking, speaking with Mr Cash, and incorporating the information he provided in a written report back to ‘Alex.’”

Equally significant, Collins confirmed that “on occasion, some of the information passed by Mr Cash to Mr Berry and then to ‘Alex’ was confirmed to also be in the possession of a senior CCP leader.” That finding points to a direct channel between Westminster and the Chinese leadership — indicating that intelligence gathered inside Parliament reached the uppermost tier of the Party, reportedly including one of Xi Jinping’s confidants.

These findings lie at the center of what is now the most serious British espionage controversy in a generation — a direct intelligence pipeline from Westminster to Beijing’s Politburo Standing Committee, revealed in a spy case later dropped by the Crown Prosecution Service after the government could not provide the evidence required to define China as a national-security threat.

Collins’s twelve-page statement, ordered released after mounting political pressure, reveals a meticulously documented flow of information — and a blueprint for how Beijing’s intelligence and United Front networks penetrate Western democracies to neutralise lawmakers viewed as threats to China’s strategic aims. Taskings focused on Huawei’s telecom ambitions, Chinese investment in Western semiconductor infrastructure, and criticism of the genocide in Xinjiang — all issues that Cash and Berry allegedly briefed their handlers on.

But political leadership was paramount.

Collins’s statement offers a chillingly precise account of why Beijing fixated on Britain’s 2022 Conservative leadership race. The Chinese state, he wrote, viewed the contest as a live opportunity to “ascertain the possible direction of the UK government, particularly on China-related issues.” According to Collins, the interest was heightened by the prospect that “Tom Tugendhat MP, sanctioned by the Chinese state for his opinions,” might “become a minister of a department that has a significant role in shaping the UK’s China policy.”

As the evidence showed, Berry relayed that a senior Chinese Communist Party leader was personally “asking specific questions about each MP within the Conservative leadership election one by one.” This granular focus revealed how Chinese secret police sought to map Britain’s internal power shifts in real time, directing their resources “towards, or away from, a particular group of individuals.” Collins noted that such information was immensely valuable to China, which could only acquire it through “well-placed human sources such as Mr Berry and Mr Cash.”

Mr Berry’s reports to “Alex,” Collins added, indicated that “a senior CCP leader spoke about how, if certain MPs were elected, there would be consequences for UK–China relations.”

The evidence also showed that Cash reported “back-channel” efforts to soften Tugendhat’s stance on targeting Confucius Institutes—entities the United States has barred from federal funding and designated as foreign missions—central to the Chinese Communist Party’s United Front interference arm.

The Bureau’s assessment of this unprecedented Parliamentary disclosure — released after the collapse of the trial and now providing insights a court never examined — is that British counter-intelligence viewed Cash and Berry as operating within the tempo of a professional espionage pipeline: a handler issuing a request, an intermediary gathering data from a privileged Westminster contact, and intelligence moving back to Beijing quickly enough to shape day-to-day decisions.

Above all, it demonstrates that — according to Collins — the information flowing from Cash to Berry posed a grave risk to British democracy. It could have allowed Beijing to manipulate Parliament itself, shaping leadership outcomes and policy debates. Collins warned that China’s intelligence reach was such that it might have sought to block China hawk Tom Tugendhat from ascending to Conservative leadership — suggesting that Beijing sought to influence, or even pre-empt, the very office Keir Starmer now occupies.

Operating from China, Berry was allegedly tasked by “Alex,” a Ministry of State Security agent working through a front organisation. Collins wrote that “Alex” directed Berry to seek intelligence from Cash, who at the time served as Director of the China Research Group (CRG) — the cross-party caucus founded by Tom Tugendhat and Neil O’Brien to push for tougher policy on Beijing. Collins confirmed that Cash’s role gave him “access to senior Members of Parliament, including the Chair of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee (Alicia Kearns MP) and her predecessor in that role, the now Minister of State for Security, Tom Tugendhat MP.” That access, Collins concluded, “made him well placed to obtain the information requested by Mr Berry, particularly that relating to China-related policies, which was ultimately passed to ‘Alex.’”

The CRG had been sanctioned by Beijing in March 2021, alongside nine UK individuals and three entities, after its founders publicly criticised human-rights abuses in Xinjiang. Collins noted that this “illustrates the extent to which the CCP deemed the CRG to pose a threat to China,” and that Cash’s employment “would therefore have been of interest to the Chinese state.” The intelligence motive was plain: the CRG represented the intellectual nucleus of Britain’s hawkish China stance. By recruiting Berry to handle Cash, Beijing’s intelligence services had positioned themselves to monitor — and potentially influence — the very MPs shaping the UK’s China policy.

By any measure, the release of these statements is a political detonation — a red alert for Western capitals. Parliament forced their disclosure after weeks of uproar over the collapsed espionage prosecution, dropped when prosecutors admitted they could not produce evidence explicitly defining China as a national-security threat.

Starmer, accused by Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch of a “cover-up,” authorised the declassification of all three witness statements from the Deputy National Security Adviser. Together, they form a rare continuum, revealing that Chinese espionage poses the most significant state-based threat to the United Kingdom’s security and democratic integrity, even as successive governments have sought to preserve trade with Beijing.

In detail, the newly disclosed evidence traces Ministry of State Security access into the 2022 Conservative leadership race, when Beijing’s focus shifted from policy to power. Collins records that Cash told Berry that Tugendhat was “almost certainly” due a Cabinet position from Rishi Sunak, and warned that the information was “very off the record.” Within a week, Berry transmitted it anyway, in a report titled “Open Attitudes between Government.” Another entry shows Cash informing Berry that Jeremy Hunt would likely withdraw from the race and back Tugendhat — a message marked “v[ery] confidential (defo don’t share with your new employer)” — which Berry again forwarded to “Alex.”

Collins wrote that this information would allow China “to ascertain the possible direction of the UK government, particularly on China-related issues,” and to gauge “the likely outcome of the democratic process to choose the leader of the governing political party.” Beijing’s leaders, he added, were reportedly asking one by one about each MP in the leadership election, with particular attention to candidates for Home Secretary, Foreign Secretary and Security Minister — positions central to Britain’s China policy. In effect, Collins wrote, Beijing had indirect access to someone who knew and conversed with Tugendhat, a figure of “significant interest to the Chinese state.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bureau to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.