Analysis: CSIS Warned Beijing Weaponized Canola and Elections in the 2019 Meng Crisis — Is Carney’s EV Trade-Off a Replay?

OTTAWA — A high-level Canadian Security Intelligence Service assessment in June 2019 concluded that Beijing, jolted by Canada’s detention of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou, launched a “calibrated and multi-faceted pressure campaign” that blended trade coercion — including curtailing canola imports — with the detention of Canadians and clandestine interference surrounding the 2019 federal election, aiming to exert “personalized political pressure on Canada’s leadership,” with the Ministry of State Security driving the response and CSIS collection further establishing that President Xi Jinping received reports “directly from the MSS.”

The assessment — marked “SECRET” for Canadian Eyes Only and titled PRC Strategy and Tactics to Influence the Meng Wanzhou Proceedings — warned that Beijing was “actively leveraging its leading intelligence service, the Ministry of State Security, to both apply pressure and encourage dialogue with Canada on Beijing’s terms.”

It further assessed that MSS units were tasked from “high levels” to “actively respond,” spurring competition inside the service to make the “largest possible impact,” while PRC missions in Canada moved to shape the political environment ahead of the 2019 vote.

“Multiple corroborated reports confirm that PRC missions are moderating their support for the Prime Minister and other Liberal candidates,” the document says, describing an effort to exploit electoral unpredictability — and to hedge across party lines — to maximize Beijing’s leverage over politically influential Canadians.

Six years later, those warnings have acquired new relevance.

In mid-January, Prime Minister Mark Carney, on a trade mission to Beijing, reached an initial agreement that would allow China to export up to 49,000 electric vehicles into the Canadian market at a sharply reduced tariff, while China would lower tariffs on Canadian canola seed by March 1 to a combined rate of about 15%.

Reuters also reported that senior United States officials described Canada’s decision as “problematic,” warned Canada would “regret” it, and said the Chinese vehicles would not be allowed to enter the United States — casting the deal as not only an economic dispute, but a national-security and data-security flashpoint tied to connected-vehicle technology.

The Bureau is re-examining the 2019 CSIS assessment to test an uncomfortable question: is Ottawa once again confronting the same pressure dynamics Canadian intelligence described during the Meng crisis — trade leverage aimed at politically connected decision-makers, influence operations applied to Canadian democratic processes, and coercive tactics calibrated for maximum political effect — and has Beijing again secured a strategic outcome under high-pressure conditions, pulling Canada closer to its orbit and further from Washington?

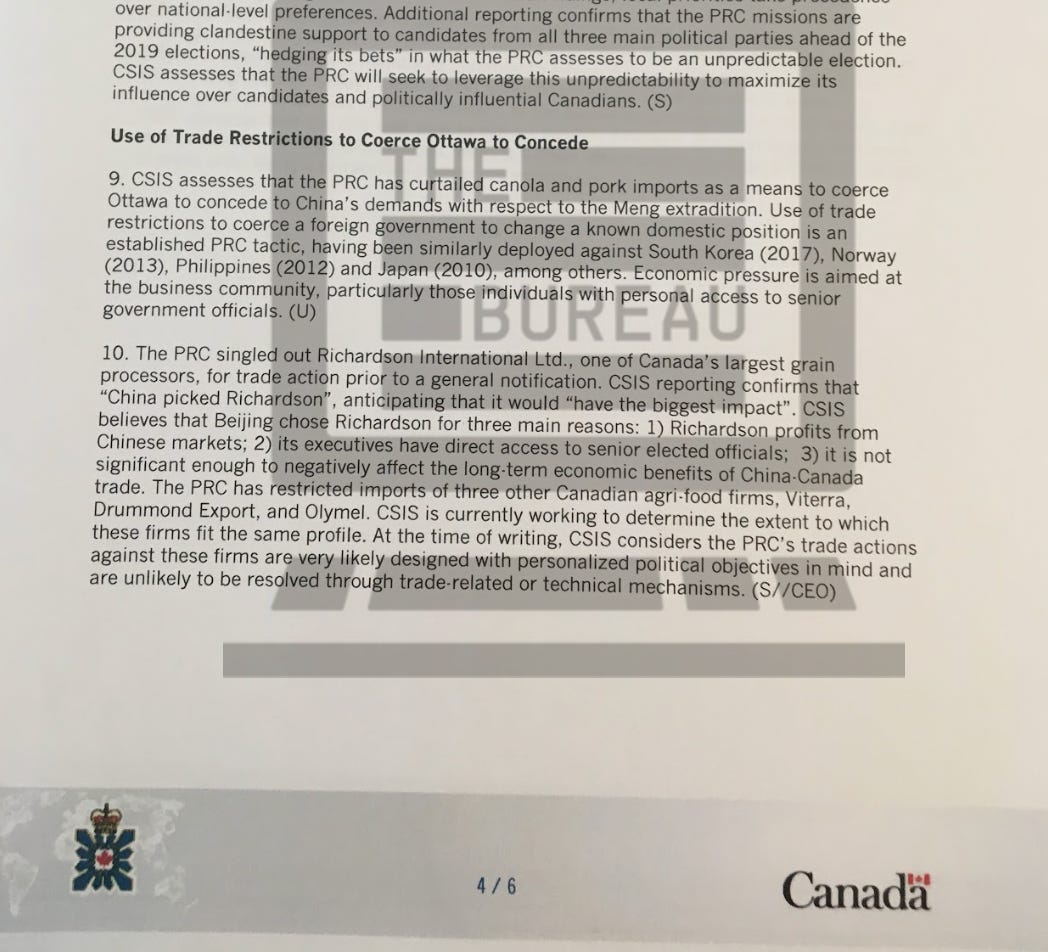

The CSIS assessment’s central claim was that Beijing treated trade not as ordinary commerce, but as coercion — a political instrument designed to force concessions.

It said the PRC “very likely imposed restrictions on imported goods from Canada as a means to coerce the Government of Canada to concede to China’s demands with respect to Ms. Meng’s extradition,” adding that “economic pressure is aimed at the business community, particularly those individuals with personal access to senior government officials.”

In concrete terms, CSIS assessed that the PRC curtailed canola imports “as a means to coerce Ottawa to concede to China’s demands with respect to the Meng extradition.”

That is what makes the document a measuring stick for the present — especially as Carney’s Beijing mission included Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe, a political figure closely tied to the commodity economy most exposed to canola leverage.

The 2019 CSIS assessment points directly at Saskatchewan’s canola trading giant Richardson International as a targeted node in Beijing’s pressure campaign.

“The PRC singled out Richardson International Ltd.,” the document states, adding that “CSIS reporting confirms that ‘China picked Richardson’, anticipating that it would ‘have the biggest impact’.”

CSIS assessed Beijing selected Richardson in part because its “executives have direct access to senior elected officials,” and because it “profits from Chinese markets.”

Beijing’s trade actions, CSIS concluded, were “very likely designed with personalized political objectives in mind” and were “unlikely to be resolved through trade-related or technical mechanisms.”

Premier Scott Moe last August publicly underscored how tightly Saskatchewan’s canola-processing economy is tied to trade access—particularly with China—in remarks delivered at Richardson Oilseed in Yorkton, North America’s largest canola-crushing facility.

Announcing provincial support to cover up to half the cost of upgrading the seven-kilometre Grain Millers Drive corridor serving Richardson, Grain Millers, and Louis Dreyfus, Moe said the route “supports so much of our exporting industries,” and pointed to the scale of the China market, saying “about $4 billion of agricultural products flow to China each year from Saskatchewan,” while describing canola as a “$45-billion industry” that employs “more than 200,000 Canadians.”

In 2019, CSIS summarized Beijing’s approach bluntly: alongside detentions and election interference, it assessed that Beijing sought to influence Canada’s senior leaders by “singling out politically-connected members of the business community for trade action.”

CSIS assessed that Beijing’s trade restrictions were calibrated for leverage, not rupture — designed “to exert political pressure on key decision-makers,” and “not assessed as intended to cause permanent damage to bilateral trade.”

CSIS also framed the canola-and-pork restrictions as part of an established PRC playbook — not a one-off response to the Meng crisis, but a repeatable tactic used to force governments to shift a known domestic position. In the assessment, CSIS said similar trade-pressure campaigns had been deployed against Japan (2010), the Philippines (2012), Norway (2013), and South Korea (2017), and emphasized that the pressure is aimed at the business community — particularly individuals with personal access to senior government officials.