A Senior Pentagon Veteran's Assessment: Why China's Military Purge Reveals a Dangerous and Fragile Giant

Former Defense Department China Director exposes a volatile nuclear-armed superpower that may struggle to sustain high-intensity warfare—and why Western alliance-building is the best deterrent.

OTTAWA – The arrest that shook Beijing’s military establishment came without warning. General Zhang Youxia, 75, vice chairman of China’s Central Military Commission and Xi Jinping’s childhood friend since their fathers served together in the Communist revolution, was taken into custody earlier this month on charges of leaking nuclear secrets and accepting bribes.

For Western intelligence analysts, the purge of Zhang—who has stood at Xi’s right hand through a decade of the most aggressive military expansion in modern Chinese history—raises a question more unsettling than any battlefield scenario: What happens when an emperor surrounds himself only with yes-men who dare not tell him the truth about his military’s readiness for war?

“You must have somebody around you who can say, ‘Hey Emperor, you have no clothes on,’” says Tony C. T. Hu, speaking at an exclusive briefing this week in Ottawa attended by Taiwan’s Ambassador to Canada Harry Tseng and his staff, along with two Canadian reporters.

The Bureau asked Hu—a former Defense Department China Director with deep intelligence insights and expertise on Beijing’s global warfighting and clandestine warfare capabilities—to parse the reasons for the conflict between Xi and Zhang, and whether the West could believe the narratives of a corruption or espionage crackdown currently being transmitted from Beijing.

Hu said without hesitation that the nuclear secrets accusations against Zhang were false, in his estimation. The real issue, Hu explained, was military readiness.

“Zhang recognized that 2027 is not possible,” Hu said, referring to Xi’s stated timeline for PLA readiness regarding Taiwan. “Zhang has been through warfare—he was involved in combat—so he knows what needs to be done and he already knows that China can’t do it.”

Hu explained that Zhang was one of the few people who could have told Xi the truth about PLA capabilities. “Nobody dares tell him—like General Zhang would have—’We’re not ready,’” Hu said.

Hu would know. A retired U.S. Air Force colonel who served as Senior Director for China, Taiwan, and Mongolia in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Hu spent years as the Pentagon’s point man for assessing Beijing’s military capabilities and strategic intentions. Before that, he advised a four-star general and served as a Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile officer—experience that shapes his chilling assessment of China’s rapidly expanding nuclear arsenal and the catastrophic vulnerabilities built into its design.

The Bureau attended the full presentation Hu delivered in Ottawa, including satellite imagery, strategic assessments, and operational details that paint a portrait of a superpower at a crossroads: massive in its industrial capacity and growing in its threat to the free world, yet politically fragile and unable to demonstrate it can actually command its arsenal in sustained high-intensity combat.

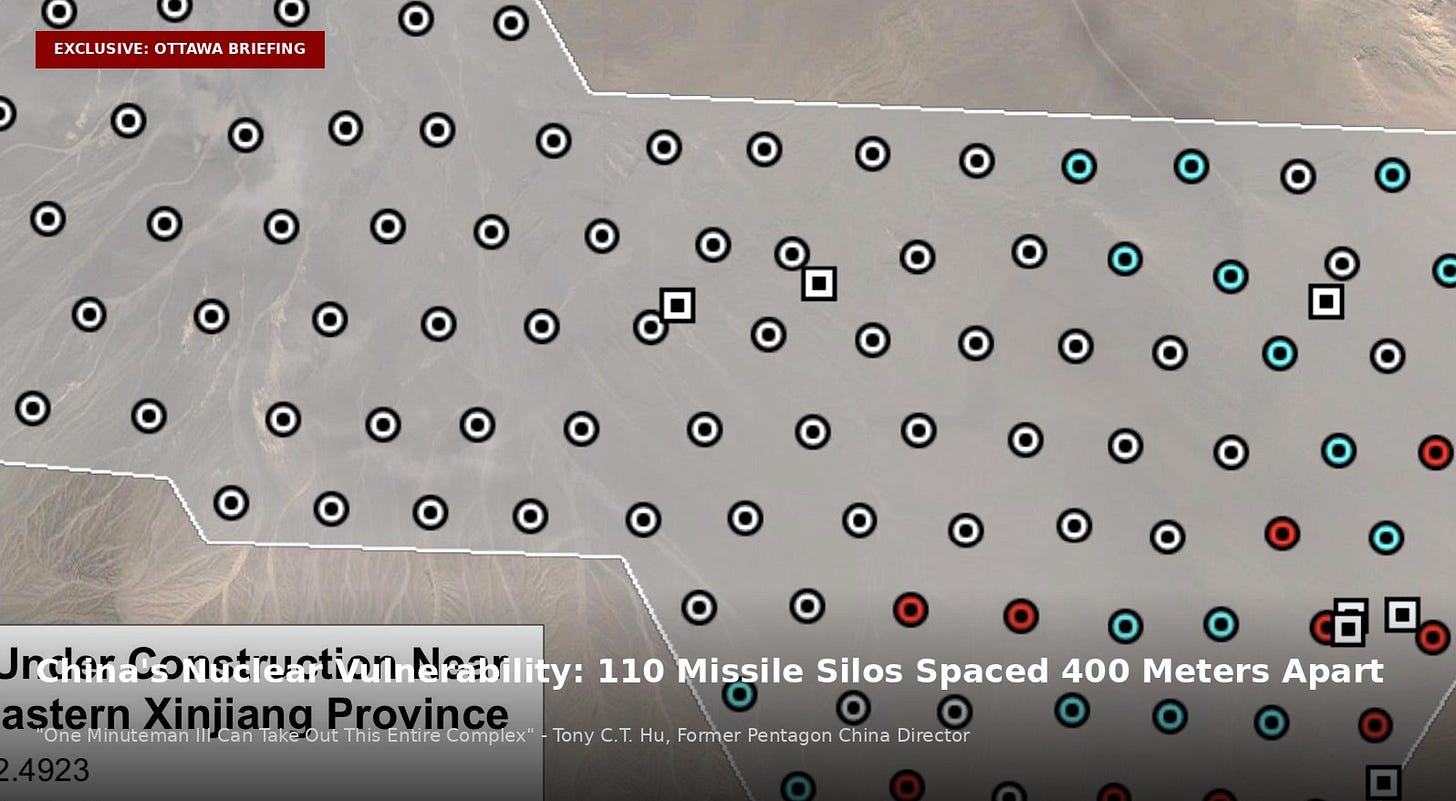

One of Hu’s most alarming revelations concerns China’s new missile fields in Xinjiang Province. Using satellite imagery and nuclear weapons effects modeling, Hu demonstrated that 110 Chinese intercontinental ballistic missile silos are spaced just 400 meters apart—so close together that a single American missile could destroy the entire complex. This creates a hair-trigger “launch on warning” posture where any perceived incoming strike could trigger a full Chinese nuclear response before verification is possible.

“All or nothing,” Hu said. “That will be the end of the world.”

On the other hand, the U.S. military has been quietly expanding its own devastating strike capabilities in the region.

In a policy shift revealed by Hu, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth told South Korea approximately three months ago that U.S. forces stationed there would gain new “flexibility”—meaning American aircraft can now strike targets deep inside northeastern China, including Beijing and the PLA’s Northern Theater Command headquarters in Shenyang, from bases on the Korean Peninsula. The change represents a fundamental expansion of U.S. deterrence architecture in Northeast Asia.

At the same time, Hu and current U.S. military leadership are conveying quiet confidence that if Washington rapidly strengthens its alliances with Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and other Indo-Pacific partners, the United States can maintain the deterrent necessary to prevent Xi from attempting the invasion many analysts believe he wants before his power consolidates further—or slips away entirely.

“Peace through strength is still the safest path to lasting peace,” Hu concluded in his briefing. But the path to that peace, he makes clear, runs through some of the most sensitive revelations about Chinese Communist Party operations that any former senior Pentagon official has made public.

Criminal Networks as Instruments of State Power

Before Hu walked his Ottawa audience through carrier strike groups and missile silos, he addressed a question that has preoccupied Western security services for years but rarely breaks into public discussion: Is China weaponizing migration?

The answer, Hu says flatly, is yes—and it involves CCP officials at the highest levels.

In the Pacific, Hu explained, Chinese migration to small island nations follows a deliberate pattern. “If you look at Tonga—it’s a country that’s only got about 20,000 people—you’ve got 4,000 Chinese there or something,” Hu explained. “They’re changing the demographic so that they can change the elections.”

But the Pacific is only the beginning, Hu says.

Asked by The Bureau whether this same strategy is being deployed in the Western Hemisphere and Latin America, Hu was unequivocal: “Same thing,” he said. “Same intention.”

The mechanism, Hu confirmed, is one The Bureau has covered in depth. It connects organized crime networks—including the sophisticated junket operations that move billions through casinos from Macau to Vancouver, Saipan and Sydney, operations The Bureau has previously tied to Belt and Road influence networks—to what he describes as “grand strategy” directed from Beijing.

Hu was careful to clarify that he was conveying his own view from years of military expertise, not the official line of the United States government.

But the exchange that follows regarding Chinese Communist Party operations is significant in any case, coming from a former senior Pentagon official with direct responsibility for China policy.

THE BUREAU: “And do you see from a military intelligence perspective that the use of underground banking channels or gray markets or criminal activity is part of that Chinese strategy? At a high level?”

HU: “Most of these criminal activities involve high-level people.”

THE BUREAU: “CCP people?”

HU: “CCP people. And they benefit from it monetarily, but they also have a grand strategy. So it’s a win-win for them, right? They’re untouchable inside of China and they just keep on doing it.”

The findings also align with recent reporting from the Taiwanese government, which has indicated that Beijing has established a fifth column on the ground in Taiwan—consisting of organized crime proxies—in preparation for any military assault from the PLA.

The implications are powerful. What Western law enforcement has often treated as discrete criminal enterprises—human smuggling networks, casino money laundering, fentanyl trafficking—Hu is describing as coordinated instruments of Chinese state power, designed to demographically and politically reshape regions from the Pacific to the Americas.

The strategic payoff is clear: when Beijing can influence the government of a small island nation through demographic change, it secures votes in international organizations, access to ports, and control over sea lanes. When it can embed organized crime networks in Latin America or the Pacific, it creates leverage over local politics and prepares the battlefield—cognitive, political, and potentially military—for future conflicts.

The Arsenal Without Mastery

Hu begins the military portion of his briefing with a slide that has alarmed Pentagon planners for years: China has overtaken the United States with the largest navy in the world.

As of 2022, China operates 351 principal combat ships compared to America’s 294. In just 15 years, Beijing has grown its fleet from 255 vessels to 351. In aircraft, the expansion is even more dramatic—from 2,100 combat aircraft in 2015 to 3,300 in 2025. China now operates three aircraft carriers with a fourth under construction.

The industrial capacity behind these numbers is something no rival can match. China produces approximately 30 warships per year and 240 combat aircraft annually. It’s a level of output that makes America’s own substantial defense industrial base look modest by comparison.

“This is tremendous,” Hu acknowledges, pulling up charts showing the trajectories. “Nobody can touch that.”

But then he pauses the presentation and pulls up a photograph that gets laughter from the Ottawa audience.

It shows a Chinese Type 96 main battle tank during a military exercise. One of its road wheels has completely fallen off. The tank sits immobilized, the detached wheel assembly lying beside it like a fallen bicycle tire.

“This is three years ago,” Hu says, letting the image speak. “Look what happened. He literally lost the wheel.”

The photo has circulated in defense analysis circles as a symbol of something more fundamental than a single maintenance failure.

“China has a lot of pretty things, but what is the reliability?” Hu continues. “They keep it such a secret. You don’t know.”

He contrasts this with American transparency, noting that the U.S. publicly reports reliability data to Congress. The F-35, he notes, is currently running at 65 percent mission-capable rate—a figure that’s publicly available despite being unflattering. China publishes nothing.

“This is the PLA’s Achilles’ heel,” Hu says. “If they go into a high-intensity conflict, can they sustain?” He notes that the reliability data needed to answer this question simply doesn’t exist publicly for Chinese systems—creating uncertainty about PLA sustainability in extended operations.

Hu pulls up another slide—a diagram titled “Military Capability”—showing how raw hardware becomes actual combat power. The inner ring contains eight essential elements: Information & Knowledge, Doctrine & Concepts, Organization, Training, Logistics & Modularity, Leadership & Education, Facilities, and Personnel. The outer ring shows the adaptive layers: Interoperability, Adaptability, and how all of this must integrate through policy.

“Numbers do not directly translate into combat capability,” Hu emphasizes. “Otherwise, it’s just a boat. It’s just a plane, it’s just a tank. You need the doctrine, the strategy, the tactics, the training, the logistics, the leadership. This is where the gap exists.”

He’s not just theorizing. The evidence comes from China’s own operations—or rather, its lack of them.

Hu notes that the last time the PLA fought a sustained military campaign was 1979, in a brief and embarrassing border war with Vietnam that exposed massive PLA weaknesses. The PLA has not fought a war in over 45 years and has no institutional knowledge of sustaining combat operations, Hu explains.

Compare that to the United States, which has been continuously engaged in military operations—from the Gulf War to Afghanistan to ongoing counter-terrorism missions—for more than three decades. American forces know how to sustain operations, have learned from failures, and have adapted doctrine based on real-world experience, Hu notes.

But the reliability question is only the beginning of Hu’s analysis. The real danger, he suggests, lies in what China has built in the deserts of Xinjiang.

The Nuclear Vulnerability

Hu pulls up a satellite image showing a massive military installation in Eastern Xinjiang Province, near the city of Hami, containing 110 intercontinental ballistic missile silos. The image, which has appeared in defense journals, reveals something that alarms Hu: the silos are spaced only 400 meters apart—roughly a quarter mile.

He contrasts this with American Minuteman III ICBM silos, which are spaced at least ten miles apart across Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming. The reason, Hu explains, is survivability. If one silo is destroyed, the others survive. That’s the fundamental principle of a distributed nuclear deterrent.

China’s Xinjiang silo field violates this principle entirely. Using NUKEMAP, a nuclear weapons effects simulator, Hu demonstrates that a single American Minuteman III missile carrying three 350-kiloton warheads—standard U.S. payload—could destroy the entire 110-silo complex with its blast radius. The United States has 450 Minuteman IIIs.

The strategic implications are devastating. China has spent billions building a nuclear arsenal that, because of poor silo spacing, is vulnerable to a relatively small first strike. This creates exactly the instability that nuclear strategists have feared since the Cold War.

Hu explains that a second-strike doctrine—the ability to absorb an enemy’s first strike and still retaliate—provides deterrence and stability. But if Chinese silos can all be destroyed in a first strike, Beijing has no second-strike capability.

The result, Hu warns, is a dangerous “launch on warning” posture. When Chinese forces detect an incoming missile—whether nuclear or conventional—they may have no choice but to launch everything before their silos are destroyed. They won’t have time to verify whether the incoming strike is nuclear.

He contrasts this with U.S. nuclear posture, designed around assured retaliation. Because American nuclear forces can survive a first strike via submarines, bombers, and widely-dispersed hardened silos, the U.S. doesn’t need to launch on warning. This creates stability and rational deterrence.

China’s compressed silo fields, by contrast, represent what Hu describes as building an arsenal for propaganda instead of strategy—creating something that makes nuclear war more likely, not less.

Multi-Domain Superiority

If China’s nuclear posture reveals dangerous inexperience, its conventional military limitations become even starker when measured against recent U.S. operations that demonstrate capabilities Beijing simply cannot replicate.

Hu pulls up a detailed timeline of Operation Absolute Resolve in Venezuela, conducted on January 3, 2025—just three weeks before the Ottawa briefing. The operation resulted in the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in Caracas and his transport to New York in under two hours total.

The operational details reveal American multi-domain warfare at its most sophisticated: 150 aircraft and helicopters positioned across 20 different bases from Puerto Rico to Honduras to carrier strike groups; 20 minutes on the ground in Caracas; B-1 bombers circling from Texas with 2,000-pound bombs as backup; real-time Presidential command and control via RQ-170 Sentinel surveillance feeds to Trump at Mar-a-Lago.

Hu emphasizes that 20 locations could have been struck simultaneously if Venezuelan forces had resisted. They knew this, which is why there was no resistance.

“Multi-domain warfare,” Hu says. “I don’t think any other country can do this.”

To prove the point, Hu describes an operation even more technically sophisticated: recent U.S. strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities occurring approximately three weeks before the briefing. Despite Iran possessing sophisticated Russian S-400 air defense systems and having spent two decades preparing for exactly this scenario, American forces operated in Iranian airspace for 90 minutes with zero resistance.

The capability integration included space-based surveillance, cyber operations ensuring communications dominance, electromagnetic spectrum control, AI-generated voice commands in Farsi that confused Iranian air defense operators, electronic warfare aircraft jamming radars, and stealth F-35s and F-22s striking targets—all coordinated in real-time.

This is the capability gap Hu returns to repeatedly: China has accumulated impressive hardware, but does it have the doctrine, training, and integration to execute these kinds of operations?

Hu points to Russia’s struggle in Ukraine as instructive. Despite having more bombers, aircraft, and tanks than Ukraine, Russia lacks the strategy and tactics for effective joint warfare. Russian forces haven’t learned the lessons the United States absorbed from the Gulf War more than 30 years ago.

This matters because China increasingly trains and coordinates with Russia. “If China’s learning from them, that’s a problem,” Hu says. “Because they’re learning the wrong lessons.”

The Korea Policy Shift

Buried in Hu’s presentation is a policy shift that has received little public attention but represents a fundamental change in U.S. deterrence posture in Northeast Asia.

“Secretary Hegseth told the South Koreans about three months ago: ‘We want to be flexible,’” Hu reveals.

The previous policy had been clear: U.S. forces stationed in South Korea defended the Korean Peninsula against North Korean aggression. They were not positioned or authorized for strikes beyond the peninsula. That restriction has been quietly lifted.

Hu explains the strategic calculus has fundamentally changed. Before, if China attacked Taiwan, the war zone might extend from Shanghai to Hainan Island. Now, U.S. forces can reach Beijing from South Korea—approximately 1,000 kilometers—and Shenyang, headquarters of the PLA’s Northern Theater Command, at about 500 kilometers.

The entire northeastern China industrial and military complex is now held at risk. If Beijing orders an attack on Taiwan, it must assume that U.S. forces from South Korea can immediately strike the Chinese homeland—not just from Okinawa or Guam, but from Korean bases that can launch aircraft with stealth cruise missiles at takeoff.

This represents what Hu calls Phase 0 operations: preparing the battlefield, ensuring the enemy knows that if they start something, they’re fighting for their own survival, not just for Taiwan.

Hu pulls up a series of photographs showing himself in different settings: standing with Taiwan Air Force pilots at Morris Air Force Base in Arizona; posing with a trophy from an international air combat competition; participating in multinational exercises with flags from Canada, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Chile, the United States, Mexico, and Singapore displayed behind the participants.

“This is what China cannot do,” Hu says. “This is the alliance advantage.”

The photos represent operational integration that takes decades to build—common communications systems, shared intelligence, interoperable equipment, and trust built through thousands of hours of joint training.

Hu notes that Taiwan pilots train at Morris Air Force Base, flying with American instructors, learning U.S. tactics, and integrating into American systems. When crisis comes, allied forces don’t have to figure out how to work together—they already know.

The same is true across the Indo-Pacific alliance structure. Japan’s Self-Defense Forces regularly train with U.S. forces in complex scenarios. South Korean and American forces have been integrated for 70 years. Australia, the Philippines, Thailand—each has deep operational relationships with the United States that activate immediately in crisis.

“We share our knowledge,” Hu emphasizes. “When one ally learns something, we all learn it. When one ally develops a new tactic, we all practice it. This is exponential capability growth.”

China, by contrast, operates largely in isolation. Its military partnerships with Russia are transactional and limited. Its relationships with North Korea and Pakistan don’t involve the kind of deep operational integration that characterizes American alliances.

Hu notes that Russia and China might conduct exercises together, but they don’t share intelligence the way U.S. allies do. They don’t trust each other the way allied democracies trust each other.

And China has never conducted expeditionary warfare at this scale, Hu notes. Chinese forces have never had to sustain operations thousands of kilometers from their borders, protect sea lanes while fighting, or coordinate logistics across an ocean. These are fundamental capability differences that no amount of hardware can overcome without decades of experience, training, and integration.

All of which returns to where this story began: the arrest of General Zhang Youxia and what it reveals about Xi Jinping’s grip on power and judgment.

There’s speculation, Hu says carefully, that Zhang was trying to clean house—to bring in people who would tell Xi the truth about military readiness. If this is accurate, Zhang’s arrest would represent Xi’s rejection of that truth, a deliberate choice to surround himself only with officers who confirm his assumptions rather than challenge them.

But there’s another interpretation that may be even more destabilizing: that Zhang’s purge was a preemptive counter-coup, that Zhang had seen enough of the COVID disasters, economic problems, and diplomatic isolation to decide Xi had to go.

If Xi believed this, then Zhang’s arrest makes perfect sense as self-preservation. But it also means Xi now stands atop a military establishment where the most senior and experienced officers either fear him or are gone.

The Central Military Commission, Hu notes, is now basically empty except for Xi and one anti-corruption official. Who will plan operations? Who will tell Xi if something won’t work?

This is the paradox at the heart of China’s military threat: it is simultaneously more dangerous and more brittle than at any point in recent history. More dangerous because the arsenal is real—the ships, aircraft, missiles, and nuclear warheads are all tangible and growing. More brittle because the political structure commanding that arsenal is increasingly unstable, isolated from accurate information, and prone to catastrophic misjudgment.

This is why deterrence matters more than ever, Hu emphasizes. Because the West can no longer count on rational decision-making in Beijing.

Excellent article.

OMG. This reads like a mentally indigestible Rand report released from Confidential and Secret. Super duper Cooper!